I am often asked why the older recordings are better. By older people usually mean the stereo orchestral and operatic recordings made between the late 1950s and early 1970s. I am not sure that I know the answer, but the observation is true in many respects, and recordings from the golden age of stereo continue to provide stiff competition to modern recordings. The venues and techniques used for some of these older recordings are documented and perhaps reveal the secret of their quality.

Strauss: Ein Heldenleben

Chicago Symphony Orchestra / Fritz Reiner

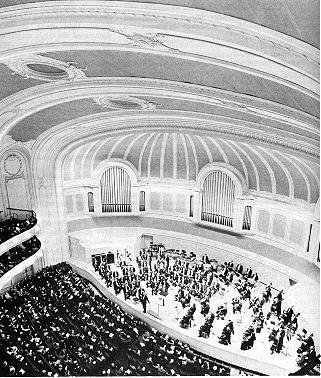

6 March 1954 : Orchestra Hall, Chicago

This recording was made on a single day and still sounds magnificent over 55 years later. It was made with only two spaced microphones. Sometimes the sound is a little edgy in the treble, probably as a result of the microphone type used, but this can easily be tamed. As can be seen, the stage in Chicago is wider than it is deep.

Beethoven: Symphonies Nos. 1-9

Philharmonia Orchestra / Otto Klemperer

21/22 October 1957 : Kingsway Hall, London

Klemperer recorded all the Beethoven symphonies in stereo between 1957 and 1960. I find the Fourth Symphony to be the best of them all in terms of recorded sound. Kingsway Hall, which has now been demolished, had an open clear acoustic, with a sloping floor on which the players were arranged.

Ravel: Daphnis and Chloe Ballet

London Symphony Orchestra / Pierre Monteux

27-28 April 1959 : Kingsway Hall, London

This recording was also made in Kingsway Hall, the acoustics of which did vary somewhat, for reasons that were never quite clear, but which seem to have had something to do with the storerooms under the hall, which were sometimes empty and sometimes full. The interior of the hall was constructed with wood and plaster and at its best sounded very clear and clean, as here. Monteux was a fine conductor who had given the first performance of this score 47 years earlier.

Stravinsky: The Firebird

London Symphony Orchestra / Antal Dorati

7 June 1959 : Watford Town Hall

This Mercury 3-channel recording was made by the legendary Bob Fine, with three microphones in a hall on the northern outskirts of London, now called the Watford Colosseum. Similar in design to the Walthamstow Hall described below, the clear acoustics make things very easy for the engineer.

Brahms: Symphony No. 3

Columbia Symphony Orchestra / Bruno Walter

27 & 30 January, 1960 : American Legion Hall, Los Angeles

Like Klemperer, Walter recorded most of his repertoire in his last years, beginning in 1958 with the Beethoven symphonies. Many critics have dismissed these recordings, claiming that the orchestra was sub-standard, but I have never agreed. A small number of microphones was used with a relatively small orchestra arranged on the floor of the hall.

Vaughan Williams: Fantasia on a Theme of Thomas Tallis

Sinfonia of London / Sir John Barbirolli

17 May 1962 : TheTemple Church, London

To avoid traffic noise, this recording was made at night — by Neville Boyling who engineered many fine EMI recordings. The acoustics of the Temple Church were ideal for the work. Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro which accompanies it on the same LP or CD was recorded in Kingsway Hall in November 1962, as the Temple Church would not have been as appropriate for it. The picture above illustrates this session.

Verdi: Four Sacred Pieces

Philharmonia Orchestra & Chorus / Carlo Maria Giulini

10, 11, 12, & 13 December 1962 : Kingsway Hall, London

Clear and clean with an uncanny ability to project the sound of the silence in the rests, this recording was also made in Kingsway Hall and has a remarkable dynamic range for analog tape. The layout of the performers was similar to that used for the Vaughan Williams recording discussed below. The picture above does not come from this recording, but shows the hall with a chorus in the upper balcony (not used for this recording) and the orchestra on the floor of the hall.

Wagner: Götterdämmerung

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra / Solti

spring and autumn of 1964 : Sofiensaal Vienna.

This was the third opera of Wagner’s Ring cycle to be recorded by Decca, and represents the highest recorded quality of the whole series. Vienna’s Sofiensaal, since destroyed by fire, was mostly used as a ballroom. The performers were spread over the floor of the large hall, with off-stage instruments recorded simultaneously in a smaller hall. The sound was judged entirely through the loudspeakers and carefully balanced in stereo on the spot.

Verdi: Don Carlos

Royal Opera House Covent Garden Orchestra / Giulini

18-31 August 1970 : Walthamstow Assembly Hall

As can be seen in the above photo, the wooden floor of the main hall of this art deco building is spacious — 97.5 ft.by 60ft. The orchestra has plenty of room and there were no ensemble problems between stage, orchestra and off-stage band.

Vaughan Williams: A Pilgrim’s Progress

London Philharmonic Orchestra / Sir Adrian Boult

November 1970 and January 1971 : Kingsway Hall, London

I confess to having been a member the team that recorded these last two examples. Although more microphones were used in this recording than in earlier recordings in this hall, they were mixed direct to stereo. The orchestra is oriented in the opposite direction from those in the other Kingsway Hall photos shown here, with the soloists and small chorus on stage.

I have not posted any MP3 files because this format cannot do justice to the recordings discussed.

What do these recordings have in common?

1. The conductors were all well-routined and conducting their well-honed repertoire with orchestras that were used to working with them.

2. Mostly the recordings were not made in concert halls with the orchestra seated onstage. Large recording studios and halls allow the orchestra to be seated optimally on the open floor. In particular, the bass instruments gain in fundamental tone when on a solid floor rather than a hollow stage. Often the sections of the orchestra are separated more than they would be on a concert stage. This probably enables the sections to hear themselves better and play optimally, and undoubtedly enables one section to hear another well. When there are problems with ensemble caused by poor acoustics, the players complain loudly about not hearing each other, which was never the case in these recordings. Screens, that would look unsightly in a concert, were used to reflect the sound towards the microphones as necessary.

3. A small number of microphones was used, of a type that was designed in Germany and Austria around 1950 (M49, M50, C12, U47/U48, etc). These microphones do not have a flat frequency response, emphasizing the treble range on axis. When positioned carefully by ear (usually above the players) they produce a solid sound which has a strong fundamental tone.

4. The output of the microphones was mixed directly to stereo. Thus any problems would be noticed at the time of recording.

Does this answer the question? Maybe not, but it is humbling to note that digital technology, while it has enabled the public to hear better quality in the home, has not produced better recordings than those made before its introduction about 30 years ago.

© David Pickett and davidpickett, 2009. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to David Pickett and davidpickett with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

This is a wonderful sublink. Do you recall the early Mercury Living Presence recording of a Piston Symphony – I think 2 – in the Eastman Theater – there was something about a single U47, apparently, in a good hall – that really delivered the goods.

Thank you for your comment, Jim. I do not recall this particular LP, which was a single point mono recording. When Mercury started recording in stereo they just increased the number of U47s to three, and positioned them pretty much in the same spot. There is more interesting information here, though I would disagree with the theory of digital recording espoused!

I am intrigued by all this and never cease to be amazed by these older recordings. Ironically the technology for LP vinyl replay in terms of turntables, tonearms, cartridges and pre-amps has advanced tremendously since CDs became the norm. Listening to my Klemperer Beethoven Symphonies cycle once again is truly captivating experience and you somehow feel directly linked to the performance being somehow aware of the acoustic and background ambiance. It would be interested to know how the recording engineers would rate the sound when played back on todays equipment in terms of tonal balance?

I recall hearing a pressing of Klemperer’s recording of Beethoven IV in a store once. It was done by Direct Metal Mastering and sounded so different from the original that I didnt recognise it at all. I have not heard the latest manifestations of these recordings on CD, so I do not know if they sound like Klemperer. At the time that I was working with EMI we were all aware that the sound of the LP pressings was inferior to that of the mastertapes. We had pretty good calibrated disc replay equipment. Perhaps the modern equipment gets better results, I do not know. The very best Klemperer recordings (the Beethoven symphonies, the Wagner extracts, Bruckner 5 and 6, etc) certainly reproduced his unique sound on the mastertapes.

This gives a wonderful picture of the the recordings which were made during those years.

Were you part of the EMI recording team for Brahms’ German Requiem conducted by Otto Klemperer, recorded at Kingsway Hall in late 1961?

No. That recording was made while I was still a schoolboy! I remember listening to it with great pleasure when it came out. It is still strongly recommended in surveys of recordings of the work by those critics who can live with the fact that a 50 year old recording can still hold its head up alongside a recent one.

Also, would you be able to upload your pictures of Kingsway Hall to its Wikipedia page?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingsway_Hall

There seem to be no pictures of KH on the internet except yours…and it’s now sadly been demolished

I could not agree more that the recordings chosen indicate that analog techniques could, in the hands of a skilled engineer, superlative recording venue, and of course, the best musicians, produced memorable disks that have more than stood the test of over a half century of time! RCA’s Lewis Layton, in my opinion, engineered some of the most amazing recordings, includling the Prokofiev Alexander Nevsky score, played by the Chicago Symphony and conducted by Fritz Reiner. And Kenneth Wilkinson’s fabulous Kingsway Hall recordings with Charles Gerhardt and the National Philharmonic o\Orchestra resurrected wonderful film music scores, faithfully restored by both Mr. Gerhardt and his collaborator, Christopher Palmer. Bob Fine’s incredible Merury Living Presence disks continue to delight this listener, some dating back to the mid ’50s. My new analog “rig,” featuring a SOTA turntable, Sumiko arm and Denon moving coil cartridge, bring my treasured records into an ever clearer light. Fortunately, I handled my disks very carefully over the years, and their clean surfaces allow the music inscribed upon them to shine!

But, digital technology, again with the right artists and engineers, can be equally satisfying. The work of engineers Jack Renner and Tony Faulkner, as well as film scoring mixer Shawn Murphy, have left a legacy of modern sound reocrdings and sound tracks that, in my opinion, validate the premise that new technology can bring one ever closer to a convincinig replica of an actual performance.

I agree about the Mercury and other recordings you mention. However, I think that the issue of digital versus analog is a red herring. High quality music-making in a good acoustic provides an excellent start. If that is recorded with good microphones in the right places and balanced by someone with excellent ears and musical taste, the results are not affected by the storage medium. Having said that, I do think that 24-bit recording is essential to be comparable with the best analog recordings.

It was one of the worst day in musical history when Kingsway Hall was demolished. What a fantastic acoustic and what a magnificent organ! I often think this building would have made a superb recording museum given its history, if no longer considered it for recording per se(!) The other sad day was the abandonment of Quadraphonic sound, which having finally having found decent decoders that worked, was abandoned. The recordings made in the 70s era in Quadraphonic SQ are glorious!! Madness to stop.

Now we have digital dryness and clinical sound. Progress? Never!!!

It has to be recalled that the space that was used for recording in Kingsway Hall was only a relatively small part of the building. There were also extensive and tall rooms below ground. It seems that these were largely used for storage, and there was often speculation among the engineers as to whether the actual amount of “stuff” in these rooms was what caused the acoustics of the hall itself to vary somewhat from time to time.

I would disagree with you concerning the organ. I improvised on it on occasion and it was rather a dull sound with some loud pedal flue pipes and a large tuba, and little else to commend it. The bells in the Auto da fé scene on Giulini’s recording of Don Carlos were played by me on that instrument and added in post-production!

As to Quadraphonic sound, it is has been reborn as Ambisonics and there are some fine surround recordings available on SACD, DVD-A and as FLAC files using this and other techniques. These media provide a more faithful reproduction of the recording than SQ ever did, and there is no reason for surround to be dry or clinical: that is a decision made by engineers and producers. Try, for instance, the recording of Widor’s Mass on SACD (JAV158), recorded in St. Sulpice in Paris. Now there’s a fine organ; and, played over a decent system, the performance and recording are thrilling.

I agree concerning Quadraphonic sound. Indeed, one label at least has reissued many old &0s recordings on SACD. They are magnificent. SACD in general is very good, although I note on certain recording the front channels are far too dominant. At least we have again a four channel discreet system, so yes! As to the organ at Kingsway Hall, it was indeed a child of its time, with a thick chorus, obligatory Tuba and enormous pedal flues right out of the Edwardian era! With such organs (and I play a very similar one by Hill, Norman and Beard regularly) the answer is often to reduce 8 foot tone. I often use two 4 foots on the great against the swell for example, and save the rest for crashes!! Kingsway Hall should never have been scrapped though, and other recording venues today are either uninterestingly dead or two reverberant. All best, Richard Astridge, Liverpool

I ‘ve come across this blog by coïncidence: I searched for information concerning the acoustics of Kingsway Hall, and found a very useful summary over here. Very nice reading! (I ‘m a graduated acoustics engineer and freelance sound engineer, hence my interest.)

Hi I’ve only just come across this site and the correspondence. If you are interested in the acoustics at KH perhaps you could try and find a copy of an article written by Denis Vaughan who was one of Thomas Beecham’s assistants. It was published by Wireless World In May 1982 Pages 30-34. If you have trouble finding a copy email m here:

gmdf3@aol.com

The Wiki article referred earlier was edited by me {I did not post the original] and also I wrote the 3 articles cited in the references. I spent many months researching KH before writing those articles and they did not use all the material I gathered. One reason was the space available in the magazine but also it was copyright fees payable to various organisations for documents and photographs. I did think of writing a book but these fees killed that off! I paid for a number of photos from EMI archives at Hayes and so perhaps they could be uploaded. There is a lot of material about the Mission at the London Metropolitan Archive and also at Camden Library in the Theobald’s Road.

Sir:

Thank you VERY much for your site.

I remember the KINGWAY HALL and the Stoll Theatre and Kingsway Tramway from my childhood. My parents often took me to these places. I am writing a piece for one of my websites about KINGSWAY and the glorious places that were once part of it:

LONDON TALES: http//cspj-londontales.blogspot.com

Charles S.P. Jenkins.

Yes. A great pity this building, one of the best recording studios in the world, could not have been preserved. But perhaps we have enough recordings already! Who needs the vast choice of recordings of core repertoire, such as was laid down already here in this hall? One hundred books by 100 authors is not the same as 100 recordings of the same masterpiece.

I was present at Andre Previn’s recording of the Vaughan Williams ‘Sea Symphony’ at KH. The sound in the hall was magnificent, but the RCA recording – certainly in its vinyl incarnation – was highly disappointing due to the decision to squeeze the entire work onto a single disc! The CD seems to be unavailable, so I can’t comment whether the results on that are improved or not.

I think there was so much history surrounding Kingsway Hall that it should have been preserved for future generations to see the location of so many classic recordings. Ironically, the other exceptional recording venue, used I think exclusively by Decca, the Sofiensaal in Vienna is also gone. Some of the finest engineered recordings ever were made there but now both places are just a memory. Recently I heard a remastered recording of Beethoven’s 3rd Symphony, VPO/Schmidt-Isserstedt recorded in Vienna (c.1966) and the sound blew me away, have never anything as good from a purely digital recording.

I was fortunate as a boy to take part in the first recording of Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, by Decca under the composer, in Kingsway Hall. This site really brought it back to me. This iconic recording by Kenneth Wilkinson, produced by John Culshaw, is still electrifying – both for performance and technically. Kenneth Wilkinson was very friendly and patient with us boys, letting us into the control room when we must have been a real pain!

Ian Meyrick

I was intrigued to find this thread and remember Kingsway Hall for many different reasons.

I lived at Kingsway Hall with my Mum, who worked for the West London MIssion, from 1969 to 1981 when the Mission moved out and we all had to leave.

It was an amazing place to live with its wonderful parquet floored entrance hall and Dove above.

Our flat was beautiful and the lifts in the front and back of the building were a joy.

We were the envy of a lot of friends in that we had the open roof to play on and sunbathe!

The only bits that I remember less fondly where the warren of dark corridors and little rooms off of the front staircase and surrounding the lift and walking through the chapel at night in the dark was a bit spooky for a child.

The worst thing I ever remember about living there was when the IRA let off a bomb in Wild Court.

However, one of the greatest bits I remember and still gives me the shivers to this day is the recording of the ‘Damian’ music which echoed round the building!

So sad to find out that the old Hall was demolished in 1998 it was truly a wonderful place to live.

Hello David, I have been reading with interest all the comments about Kingsway Hall. I was an engineer with Decca in the late 1960s/early seventies,and have many happy memories of being involved with records ranging from Joan Sutherland to one of the last recordings of Rubenstein, with Barenboim conducting.He insisted on the balance of piano to orchestra to be so much in favour of the piano as to be overpowering but it was decided to release it as he wanted it !!

As for the hall itself….On a hot day the control room,which was behind the organ got so hot that in between takes we used to open the fire doors to let the fresh air in and some artists even went out into the alley way down the side to cool off.

Pavarotti once refused to sing unless he could watch the football,so someone was duly despatched to obtain one,The associate Minster to Lord Soper, Kenneth Whitcher lent his portable television on condition that Pavarotti signed it …he duly did.Unfortunatley Kenneth’s cleaning lady thought someone had defaced the television and proceeded to scrub it clean.!!

Kingsway was also a venue for the Blood donor service,and I remember getting a massive splinter in my finger and being rushed off to a nurse to have it removed with a scalpel….happy days indeed.

I agree that while digital recording has improved enormously over the years there is still something very special about these analogue classics. For me Decca had the edge over their rivals in the 60’s, the Sofiensaal was the ultimate venue for large scale works such as the Ring and Verdi’s Requiem and I’ve always loved the sound they produced in the 60’s from their Victoria Hall, Geneva, recordings. Another venue where Decca excelled was the Sala Santa Cecilia, Rome. The recording quality of the 1959 “La Boheme” still sounds extraordinary almost 60 years on!!